This post describes the garbage collection technique called concurrent marking. The optimization allows a JavaScript application to continue execution while the garbage collector scans the heap to find and mark live objects. Our benchmarks show that concurrent marking reduces the time spent marking on the main thread by 60%–70%. Concurrent marking is the last puzzle piece of the Orinoco project — the project to incrementally replace the old garbage collector with the new mostly concurrent and parallel garbage collector. Concurrent marking is enabled by default in Chrome 64 and Node.js v10.

Background

Marking is a phase of V8’s Mark-Compact garbage collector. During this phase the collector discovers and marks all live objects. Marking starts from the set of known live objects such as the global object and the currently active functions — the so-called roots. The collector marks the roots as live and follows the pointers in them to discover more live objects. The collector continues marking the newly discovered objects and following pointers until there are no more objects to mark. At the end of marking, all unmarked objects on the heap are unreachable from the application and can be safely reclaimed.

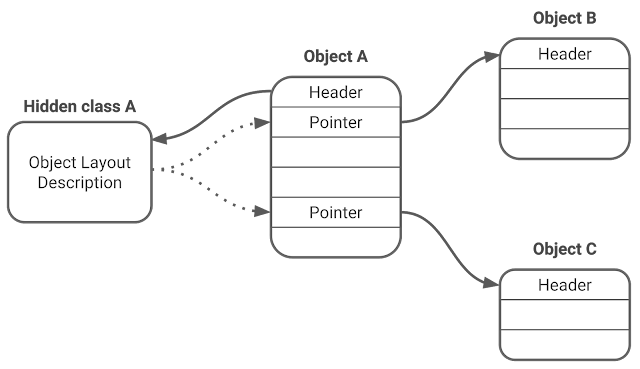

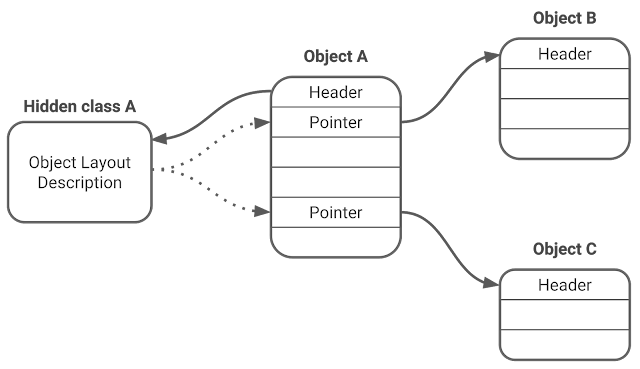

We can think of marking as a graph traversal. The objects on the heap are nodes of the graph. Pointers from one object to another are edges of the graph. Given a node in the graph we can find all out-going edges of that node using the hidden class of the object.

|

| Figure 1. Object graph |

V8 implements marking using two mark-bits per object and a marking worklist. Two mark-bits encode three colors: white (00), grey (10), and black (11). Initially all objects are white, which means that the collector has not discovered them yet. A white object becomes grey when the collector discovers it and pushes it onto the marking worklist. A grey object becomes black when the collector pops it from the marking worklist and visits all its fields. This scheme is called tri-color marking. Marking finishes when there are no more grey objects. All the remaining white objects are unreachable and can be safely reclaimed.

|

| Figure 2. Marking starts from the roots. |

|

| Figure 3. The collector turns a grey object into black by processing its pointers. |

|

| Figure 4. The final state after marking is finished. |

Note that the marking algorithm described above works only if the application is paused while marking is in progress. If we allow the application to run during marking, then the application can change the graph and eventually trick the collector into freeing live objects.

Reducing marking pause

Marking performed all at once can take several hundred milliseconds for large heaps.

Such long pauses can make applications unresponsive and result in poor user experience. In 2011 V8 switched from the stop-the-world marking to incremental marking. During incremental marking the garbage collector splits up the marking work into smaller chunks and allows the application to run between the chunks:

The garbage collector chooses how much incremental marking work to perform in each chunk to match the rate of allocations by the application. In common cases this greatly improves the responsiveness of the application. For large heaps under memory pressure there can still be long pauses as the collector tries to keep up with the allocations.

Incremental marking does not come for free. The application has to notify the garbage collector about all operations that change the object graph. V8 implements the notification using a Dijkstra-style write-barrier. After each write operation of the form object.field = value in JavaScript, V8 inserts the write-barrier code:

write_barrier(object, field_offset, value) {

if (color(object) == black && color(value) == white) {

set_color(value, grey);

marking_worklist.push(value);

}

}

The write-barrier enforces the invariant that no black object points to a white object. This is also known as the strong tri-color invariant and guarantees that the application cannot hide a live object from the garbage collector, so all white objects at the end of marking are truly unreachable for the application and can be safely freed.

Incremental marking integrates nicely with idle time garbage collection scheduling as described in an earlier blog post. Chrome’s Blink task scheduler can schedule small incremental marking steps during idle time on the main thread without causing jank. This optimization works really well if idle time is available.

Because of the write-barrier cost, incremental marking may reduce throughput of the application. It is possible to improve both throughput and pause times by making use of additional worker threads. There are two ways to do marking on worker threads: parallel marking and concurrent marking.

Parallel marking happens on the main thread and the worker threads. The application is paused throughout the parallel marking phase. It is the multi-threaded version of the stop-the-world marking.

Concurrent marking happens mostly on the worker threads. The application can continue running while concurrent marking is in progress.

The following two sections describe how we added support for parallel and concurrent marking in V8.

Parallel marking

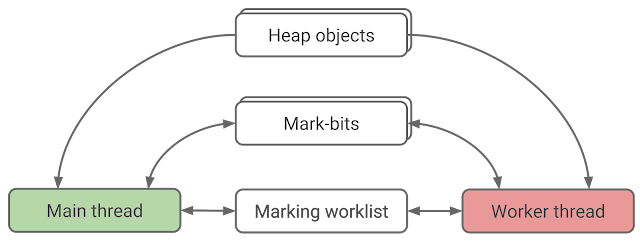

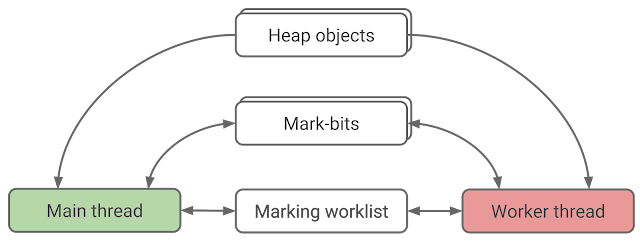

During parallel marking we can assume that the application is not running concurrently. This substantially simplifies the implementation because we can assume that the object graph is static and does not change. In order to mark the object graph in parallel, we need to make the garbage collector data structures thread-safe and find a way to efficiently share marking work between threads. The following diagram shows the data-structures involved in parallel marking. The arrows indicate the direction of data flow. For simplicity, the diagram omits data-structures that are needed for heap defragmentation.

|

| Figure 5. Data structures for parallel marking |

Note that the threads only read from the object graph and never change it. The mark-bits of the objects and the marking worklist have to support read and write accesses.

Marking worklist and work stealing

The implementation of the marking worklist is critical for performance and balances fast thread-local performance with how much work can be distributed to other threads in case they run out of work to do.

The extreme sides in that trade-off space are (a) using a completely concurrent data structure for best sharing as all objects can potentially be shared and (b) using a completely thread-local data structure where no objects can be shared, optimizing for thread-local throughput. Figure 6 shows how V8 balances these needs by using a marking worklist that is based on segments for thread-local insertion and removal. Once a segment becomes full it is published to a shared global pool where it is available for stealing. This way V8 allows marking threads to operate locally without any synchronization as long as possible and still handle cases where a single thread reaches a new sub-graph of objects while another thread starves as it completely drained its local segments.

|

| Figure 6. Marking worklist |

Concurrent marking

Concurrent marking allows JavaScript to run on the main thread while worker threads are visiting objects on the heap. This opens the door for many potential data races. For example, JavaScript may be writing to an object field at the same time as a worker thread is reading the field. The data races may confuse the garbage collector to free a live object or to mix up primitive values with pointers.

Each operation on the main thread that changes the object graph is a potential source of a data race. Since V8 is a high-performance engine with many object layout optimizations, the list of potential data race sources is rather long. Here is a high-level breakdown:

- Object allocation.

- Write to an object field.

- Object layout changes.

- Deserialization from the snapshot.

- Materialization during deoptimization of a function.

- Evacuation during young generation garbage collection.

- Code patching.

The main thread needs to synchronize with the worker threads on these operations. The cost and complexity of synchronization depends on the operation. Most operations allow lightweight synchronization with atomic memory accesses, but a few operations require exclusive access to the object. In the following subsections we highlight some of the interesting cases.

Write barrier

The data race caused by a write to an object field is resolved by turning the write operation into a relaxed atomic write and tweaking the write barrier:

write_barrier(object, field_offset, value) {

if (color(value) == white && atomic_color_transition(value, white, grey)) {

marking_worklist.push(value);

}

}

Compare it with the previously used write barrier:

write_barrier(object, field_offset, value) {

if (color(object) == black && color(value) == white) {

set_color(value, grey);

marking_worklist.push(value);

}

}

There are two changes:

- The color check of the source object (

color(object) == black) is gone.

- The color transition of the

value from white to grey happens atomically.

Without the source object color check the write barrier becomes more conservative, i.e. it may mark objects as live even if those objects are not really reachable. We removed the check to avoid an expensive memory fence that would be needed between the write operation and the write barrier:

atomic_relaxed_write(&object.field, value);

memory_fence();

write_barrier(object, field_offset, value);

Without the memory fence the object color load operation can be reordered before the write operation. If we don’t prevent the reordering, then the write barrier may observe grey object color and bail out, while a worker thread marks the object without seeing the new value. The original write barrier proposed by Dijkstra et al. also does not check the object color. They did it for simplicity, but we need it for correctness.

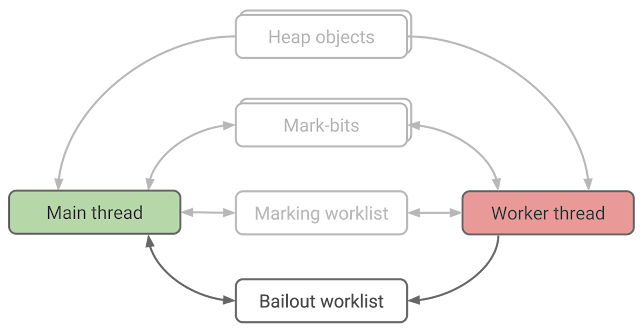

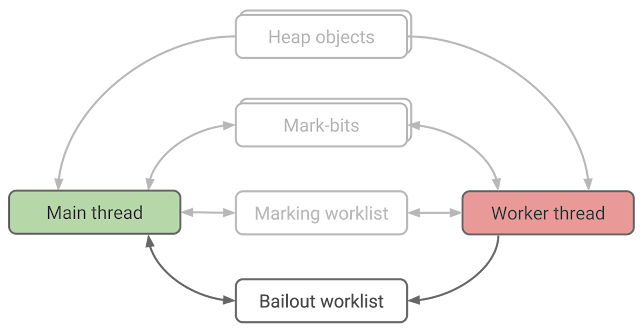

Bailout worklist

Some operations, for example code patching, require exclusive access to the object. Early on we decided to avoid per-object locks because they can lead to the priority inversion problem, where the main thread has to wait for a worker thread that is descheduled while holding an object lock. Instead of locking an object, we allow the worker thread to bailout from visiting the object. The worker thread does that by pushing the object into the bailout worklist, which is processed only by the main thread:

|

| Figure 7. The bailout worklist |

Worker threads bail out on optimized code objects, hidden classes and weak collections because visiting them would require locking or expensive synchronization protocol.

In retrospect, the bailout worklist turned out to be great for incremental development. We started implementation with worker threads bailing out on all object types and added concurrency one by one.

Object layout changes

A field of an object can store three kinds of values: a tagged pointer, a tagged small integer (also known as a Smi), or an untagged value like an unboxed floating-point number. Pointer tagging is a well-known technique that allows efficient representation of unboxed integers. In V8 the least significant bit of a tagged value indicates whether it is a pointer or an integer. This relies on the fact that pointers are word-aligned. The information about whether a field is tagged or untagged is stored in the hidden class of the object.

Some operations in V8 change an object field from tagged to untagged (or vice versa) by transitioning the object to another hidden class. Such an object layout change is unsafe for concurrent marking. If the change happens while a worker thread is visiting the object concurrently using the old hidden class, then two kinds of bugs are possible. First, the worker may miss a pointer thinking that it is an untagged value. The write barrier protects against this kind of bug. Second, the worker may treat an untagged value as a pointer and dereference it, which would result in an invalid memory access typically followed by a program crash. In order to handle this case we use a snapshotting protocol that synchronizes on the mark-bit of the object. The protocol involves two parties: the main thread changing an object field from tagged to untagged and the worker thread visiting the object. Before changing the field, the main thread ensures that the object is marked as black and pushes it into the bailout worklist for visiting later on:

atomic_color_transition(object, white, grey);

if (atomic_color_transition(object, grey, black)) {

bailout_worklist.push(object);

}

unsafe_object_layout_change(object);

As shown in the code snippet below, the worker thread first loads the hidden class of the object and snapshots all the pointer fields of the object specified by the hidden class using atomic relaxed load operations. Then it tries to mark the object black using an atomic compare and swap operation. If marking succeeded then this means that the snapshot must be consistent with the hidden class because the main thread marks the object black before changing its layout.

snapshot = [];

hidden_class = atomic_relaxed_load(&object.hidden_class);

for (field_offset in pointer_field_offsets(hidden_class)) {

pointer = atomic_relaxed_load(object + field_offset);

snapshot.add(field_offset, pointer);

}

if (atomic_color_transition(object, grey, black)) {

visit_pointers(snapshot);

}

Note that a white object that undergoes an unsafe layout change has to be marked on the main thread. Unsafe layout changes are relatively rare, so this does not have a big impact on performance of real world applications.

Putting it all together

We integrated concurrent marking into the existing incremental marking infrastructure. The main thread initiates marking by scanning the roots and filling the marking worklist. After that it posts concurrent marking tasks on the worker threads. The worker threads help the main thread to make faster marking progress by cooperatively draining the marking worklist. Once in a while the main thread participates in marking by processing the bailout worklist and the marking worklist. Once the marking worklists become empty, the main thread finalizes garbage collection. During finalization the main thread re-scans the roots and may discover more white objects. Those objects are marked in parallel with the help of worker threads.

Results

Our real-world benchmarking framework shows about 65% and 70% reduction in main thread marking time per garbage collection cycle on mobile and desktop respectively.

Concurrent marking also reduces garbage collection jank in Node.js. This is particularly important since Node.js never implemented idle time garbage collection scheduling and therefore was never able to hide marking time in non-jank-critical phases. Concurrent marking shipped in Node.js v10.

Posted by Ulan Degenbaev, Michael Lippautz, and Hannes Payer — main thread liberators